I love embroidered samplers. It doesn’t matter what era they come from, it doesn’t matter if they’re structured or not, whether they’re just marking samplers, whether they’re exquisite or rough, sophisticated or juvenile – it doesn’t matter. I love samplers!

I’m referring mainly to the extant samplers of history – those that served as records of stitches, as catalogs of designs, as testaments of skill, or all of the above. I find them charming, informative, and captivating.

Samplers serve as records of more than just stitchery, although that was certainly the primary purpose of the sampler.

Before the advent of printed designs and instructional materials, the sampler served as reference material for the embroiderer. They were repositories of design and technique.

And while they were often an exhibition of skill, they attested to the discipline, patience, and artistry of the stitcher as well.

Considered visually, the appeal of needlework samplers is fairly obvious: the stitches (sometimes intricate, sometimes simple), the play of color and design layout, symmetry or non-symmetry – all of these aspects of a sampler are often pleasing to the eye. Even rustic or naive samplers have a visual appeal. They beg the viewer to examine them. They are not just a source of aesthetic appeal, but they are often a curiosity, something that piques the viewer’s interest, even if the viewer isn’t particularly needlework-prone.

In addition to their beauty, charm, and visual appea, samplers resonate on a deeper level with us because they are part of a story. Samplers are personal. With their unique designs or layouts, their choice of motifs, of lettering, of verse, or other elements, samplers offer a glimpse into the lives, aspirations, and environment of their creators.

But they’re even part of a bigger story: they can often provide clues to the social values, religious beliefs, and societal normals of the places and eras in which their makers lived and died.

Samplers provide a window into the world of women’s domestic lives that were often overlooked in written records. They give us a glimpse of the roles, expectations, and skills that were considered vital for women in the past.

They also hint at connections between cultures. Their fabrics and threads can teach us about historical trade routes, cultural interactions and influences. Through examining fabrics, dyed threads, and diverse patterns, we can learn about socio-economic status and global connections between different cultures. As the fabrics, threads, colors, and design shift over the centuries, we gain insight into changing values, technological advancements, transitions in artistic styles and fashions, in cultural influences, and much, much more.

From the needleworker’s perspective, the story of the sampler is vital to the craft. Nothing exists in a vacuum, and needlework didn’t just spring out of nowhere. It developed slowly over time. The embroidery we do today stands on the proverbial shoulders of the “samplerists” of ages past.

Write Your Story!

If needlework samplers are a fascination for you and you’ve toyed with the idea of designing your own – maybe you want to tell your own story through a sampler or a series of samplers, but you aren’t sure where to start or how to go about it – then you might want to check out this upcoming class.

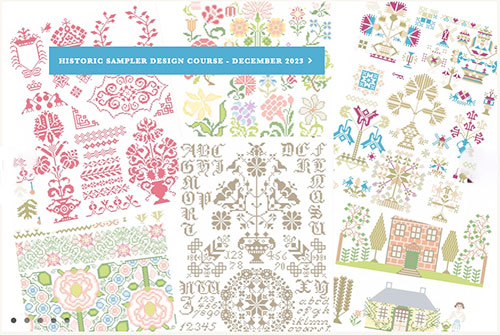

Tricia Nguyen at Thistle Threads is offering this Historic Sampler Design Course beginning in December of this year.

This is from the class description on the Thistle Threads website:

Have you wanted to design or modify your own historic-looking samplers? Perhaps you want to make a family genealogy sampler in a particular style? Have an over the top 17th century band sampler in your head? Maybe you love the monochromatic Quaker, Vierlande or French samplers and want to design your own. Have a needle book idea you wanted to design? This 4-month online course will teach the fundamentals of how to design using source material.

I think it sounds like a terrific class! Tricia has a vast wealth of historical and needlework knowledge to pass on to her students. And I think she’s also a bit of a techy wizard sort of person, which is great because you’ll learn how to use design and charting software. Never fear, though – the software (from Ursa Software) isn’t expensive or complicated. I use the MacStitch version myself (I wrote about it here way back in 2012) and I enjoy using it. And I’m not really a techy sort of person.

When I read the description of the class, I knew I had to tell you all about it. Maybe it could be your Christmas present to yourself? It’s a four month class, and I think it’s a great value. If you’re a sampler lover, why not check it out?!

I’m toying with the idea of taking it myself. Maybe we’ll run into each other in the virtual environs!

Thanks for posting, Mary! I signed up for the class!

Husband and I are 18th reenactors. I demonstrate embroidery at events by working on reproduction 18th century pieces or designs close enough to period to pass. (Current piece is a reproduction of a period seat cushion.)

Embroidery demonstration is a great way to start a conversation about women and their lives in the period. A girl learning embroidery meant that her father had the financial means for her to do so – as linen, thread, etc. had to be purchased and often a design for transfer unless it was drawn by someone in the family and she was not needed for other housework. Embroidery in the period was generally done on a frame – pieces of wood clamped together in the corners with the fabric pulled out by crossed strings along the edges out to the frame. (Frames for large pieces such as curtains, etc could be almost the size of the room in which it was being worked.) Hoops were mainly used for tambour work (name from same root as tambourine – each being a hoop) which was worked with a tiny hooked needle (think needle sized crochet hook) in chain stitch – the hoop was on a stand which freed both hands to work on top and below the fabric. (I do use a hand held hoop for my regular embroidery demonstrations.)

This means -when seeing the work of girls (or women) of the period one is seeing work done by someone of a family with the means to be afford the fabric and the threads. Young girls were learning to sew by the age of 5, but many to most did not learn embroidery due to the cost of supplies for same. These were not the daughters of an average or poor family.

What a wonderful post. You have a true gift for expressing the history of needlework and its importance as well as art and craft. I am thrilled that Tricia is offering this class.

I do have a question. Over time I’ve encountered more Samplers that tell stories using cross stitch more than any other stitch. Here you stress their importance as showcases for many different stitches. How difficult will it be to incorporate many stitches and techniques even if many of our Sampler examples are done in cross stitch ? Perhaps this is really no issue at all. We are free after all to take our needle to fabric any way we wish. But I am thinking of the conversion of our cross stitch examples into stitches of our choosing and what kind of challenge that will be for our own design purposes.

Ann

I love all your articles and the your really great instructors on doing different stitches.

Thank you